An American in Japan: Cross-Cultural Friendship, Memory, and Insight

With students at Kamikuishiki Chugakko, spring 2002

What does it mean to have a bit of your heart permanently residing in a corner of the world you were not born in and are not native to, and whose language you can only speak in small and fractured phrases? I’m sure this is a question migrants, immigrants, and wanderlust-filled travelers have asked themselves for time immemorial, and it is a question that carries increasing resonance around the world as rigid definitions of borders, boundaries, and citizenship become increasingly fraught and politicized at this moment in time.

Visiting Japan for the First Time

In my case, I began to ask myself this question during my first trip to Japan, as a 14-year-old growing up in Iowa. I had long been drawn to stories and images of and about Japan, from National Geographic features to the tragic but beautifully courageous story of Sadako, the Hiroshima teenager who died of radiation-induced cancer in the 1950s. So when I learned that my hometown was looking for youth to participate in an exchange with our new sister city in Japan, I leapt at the opportunity. That 10-day visit to Yamanashi Prefecture stands in my memory as a dazzling moment of exposure to this culture and place that I had previously only read and dreamed about, and even more significantly, to people who would become lifelong friends.

Beginning with that visit, everything from the luscious peaches and grapes grown in Yamanashi to the gleaming vistas of Fuji-san to the tranquility of the many small Shinto shrines dotting the Yamanashi countryside were a part of my lived experience and memory. So, too, were Pocari Sweat, peace signs flashed for the camera, and anime programs on TV—the more quotidian elements of daily life that were shared with me by my host family. That host family, and particularly my host sister Aska, also 14 years old, helped make Japan not just a place that I would visit on one brief occasion, but the place where part of my heart would indeed begin to reside, and that I would return to again and again in the coming years.

A Year Living in Japan

I kept in regular contact with Aska and her family over the years since my first visit to Japan, along with others I had met on that trip, and when I learned of the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Program as a college student, I knew without hesitation that I wanted to participate. Upon graduation from college in 2001, I returned to Japan via the JET Program, this time to a more rural corner of Yamanashi—Kamikuishiki-mura. Kamikuishiki immediately took my breath away with its rugged mountainous beauty and awe-inspiring views of Fuji-san, located right on its doorstep; and the students and teachers of Kamikuishiki Chugakko, where I was assigned as an Assistant English Teacher, welcomed me with great warmth and generosity. I still remember that on my first night in my new apartment—indeed, my first night ever living on my own—two of my students-to-be knocked on my door to welcome me and bring me freshly-picked peaches and grapes.

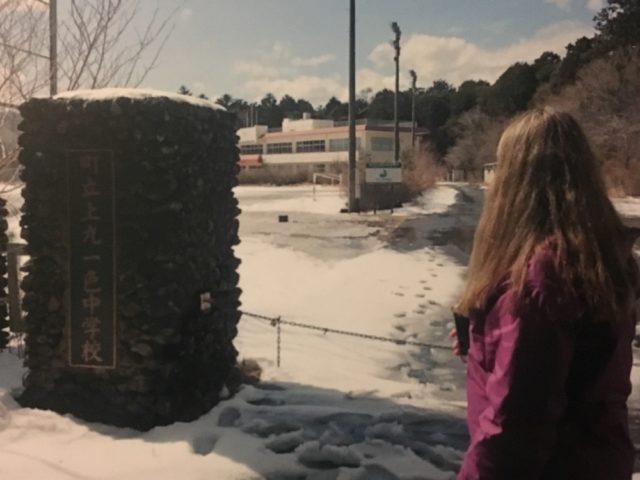

Visiting the site of Kamikuishiki Chugakko which sadly closed several years ago, spring 2018

It was one month into my year teaching in Kamikuishiki that one of the more momentous events in recent history took place, shaping both the remainder of my year in Japan and world events for decades to come. For me, the events of September 11, 2001 will always be remembered through a Japanese prism. I was in my apartment in Kamikuishiki at around 10 pm on the night of September 11, 2001, watching an evening news program, when suddenly I was seeing footage of the World Trade Center with a gaping hole in one of its towers. I stayed up all night that night talking on the phone with my family in Iowa and reading online coverage of the unfolding events, and when I arrived at the school for work the next morning, I was exhausted and emotionally drained. I will never ever forget the tremendous kindness of teachers and students alike that day and in the days to come, the teachers hovering near my desk to offer tea and words of comfort and even hugs, several of the students writing me notes of encouragement and speaking words of comfort to me in halting English, and even some of the parents bringing food for me. Most incredible of all was when the head principal, the Kocho Sensei, organized an all-school memorial honoring those who had died in the U.S. I remember him consulting maps that morning and trying to determine the exact direction of Washington, D.C., New York City, and Shanksville, Pennsylvania from Kamikuishiki Chugakko, and then arranging the entire student body in the school yard at an unusual angle so that they could face in that exact direction while observing several moments of silence.

Winter view of Enzan, Yamanashi (left) Sunny view from host family’s home (right)

What I took away from such acts of kindness and generosity by the people of Kamikuishiki, toward a people and a nation foreign to them—indeed, a nation that had committed perhaps the greatest atrocity in human history against them a mere half-century earlier—was an overwhelming sense of the power of approaching the world around us with an expansive and open and forgiving heart, as Kocho Sensei and my students and colleagues had so instinctively done. That openness of heart and willingness to see beyond the kinds of differences that lead to the building of walls and the policing of boundaries—both literal and figurative—is something that appeared to me to be in short supply in the days following September 11, 2001, when a significant number of my fellow Americans back at home were blinded by fear and rage toward the Middle East and toward followers of Islam, and eager to punch back in any way possible.

Ongoing Ties to Japan: Cultivating an Open-hearted World

Sadly, openness and expansiveness of heart also appear to be in very short supply in our current moment. At a time when instability around the world is heightening migration, and when deep divisions regularly bubble over here in the U.S. over how our country ought to treat immigrants, migrants, and visitors, we need such expansiveness and openness of heart more than ever. My dear friend Aska, having attained fluent English and earned multiple degrees in international relations, now works for the Japanese representative to the United Nations in New York, doing her part to keep the world order functioning as smoothly and as peacefully as possible. And when the two of us see each other now, as thirtysomethings, we often reminisce about our first meeting as 14-year-olds, and about the power of our mutual curiosity in each other’s cultures and our mutual planting of portions of our hearts in each other’s native countries.

With host sister Aska when we were both 14 years old

With host sister Aska, Christmas 2008

As for me, I continue to uncover new layers as I explore the question I posed in the opening to this piece, that of what it means to have a bit of your heart residing in a corner of the world far from your native land. I have visited Japan several times since teaching there on the JET Program, most recently this past spring, when I visited Aska’s family in Yamanashi and some of my former teaching colleagues in Kamikuishiki. The world feels smaller and more connected when we all remember that our hearts can live many places at once, and when the Kocho Senseis of the world help teach us that love and compassion know no boundaries.

Kirsten Crase is a postdoctoral research associate in Historic Preservation at the University of Maryland, College Park. In her free time she enjoys traveling—to Japan, when possible—exploring the Washington, D.C. area, and keeping up on current events.